the seattle pivot

CONDOMINIUM DEMAND AND HOMEOWNERSHIP LEVELS IN SEATTLE ARE MAKING A COMEBACK, BUT WILL DEVELOPERS PIVOT AND KEEP UP WITH THE TRENDS?

The second half of 2017 evidences what may be a paradigm shift in consumer trending from rent to buy. According to research by O’Connor Consulting Group, annual apartment demand in 2017 fell by 4,500 units (unexpectedly) throughout King and Snohomish counties and this decrease was concentrated into the second half of the year. Meanwhile, sales of single-family and condos in the same area swelled by more than 5,000 units—rising from 40,825 homes closed in 2016 to 45,949 in 2017. It would seem that renters are increasingly positioning themselves for capital appreciation, mortgage interest deductions and attainable ownership options for fear of being priced out with rising home prices compounded by interest rate hikes.

As of March 2018, the median home price in the Seattle metro area rose by 13% year-over-year, according to the closely watched S&P/Case-Shiller Home Price Index. In fact, Seattle has consistently led the nation in home price growth for 19 months in a row. Meanwhile, the Fed has bumped mortgage rates 6 times in the trailing 18 months, so rates now average 4.5-4.75% for a 30-year mortgage, according to Caliber Home Loans. They say several more rate increases are anticipated this year and by 2020, the average fixed rate mortgage could top 5.5%.

Throughout metro Seattle, the hunt for affordable homes has literally drained the city of single-family options, especially those priced below $700,000. That’s a popular price point because the conforming high balance loan limit in King, Pierce and Snohomish counties is $667,000, allowing homebuyers to purchase with just 5% down payment (3.5% FHA) and qualify with lower FICO scores and preferred interest rates vs. the jumbo mortgage market.

RSIR analysis of NWMLS data suggests that during Q1-2016 there were 1,454 sales of condominiums and single-family homes sold below $700,000 in the City of Seattle, but two years later during Q1-2018, that number fell to just 951 units—that’s a 35% reduction of opportunity as prices rose and supply dwindled. This is a challenging price point for developers to hit with new construction—certainly no single-family homes will pencil as land costs alone demand $700,000 or more. Townhomes offer some relief but just barely, as only two dozen newly built properties throughout Seattle are active in the NWMLS and they average 1,289 square feet at $529 per square foot, so the median asking price is still $667,000. Many more are already pending

with most new listings snapped up in just a few days on the market.

PICTURED ABOVE: The Central Townhomes presented by Realogics Sotheby’s International Realty in Columbia City are a limited collection of 24 new three-bedroom homes that are finding buyers within days of hitting the market.

Condominiums more easily hit this price point as efficiently-scaled, single-level homes offer the greatest density of housing, oftentimes with building amenities that expand the lifestyle of living in a studio or one-bedroom home. Currently in downtown Seattle, there are just 46 resale condominiums offered below $700,000 and just three in new construction inventory until 2020. Demand for new, attainably-priced condominiums was on full display on February 24th, 2018 when Da Li Development USA introduced 203 homes at KODA drawing long lines with 95% of the homes garnering reservations with another 80 second and third positions.

PICTURED ABOVE: The KODA Condominium development generated a line of prospective buyers that eagerly awaited the release of 203 homes for reservation on February 24th, 2018.

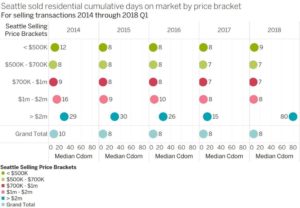

The stress on supply is very evident when comparing sales volumes and days on market for both single-family and multi-family homes at varying price points throughout the City of Seattle as follows:

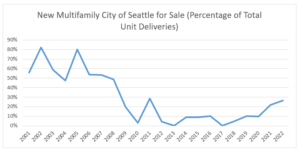

The housing demand is palpable. Seattle is the fastest-growing large city in the US, expanding by 114,000 persons since 2010. In fact, the urban population density in downtown Seattle has tripled since 2000—now estimated at approximately 80,000 residents. In the current decade approximately 30,000 multifamily housing units will be delivered in the urban core of Seattle, but 91% of that added supply will be for rent and not available for individual ownership. The dearth of new condominium supply is only further exacerbating the stress levels of eager buyers.

Fortunately, a new crop of condominiums is under development or planned throughout downtown Seattle neighborhoods. There are 10 known high-rise condominium projects (plus the potential of apartment conversions), which are anticipated to deliver in downtown Seattle between 2018 and 2022. These total more than 3,000 units; however, 641 units (or more than 21% of this future inventory) is already presold or reserved. This new product stands in stark contrast to 2017 when zero new projects were delivered. Regardless, the added supply is still considerably less than the past condo cycle between 2005 and 2010 when 4,933 new units were delivered. Market fundamentals today are considerably stronger than they were a decade ago.

PICTURED ABOVE: The SPIRE Condominium development was recently announced as a condominium for sale, which is now under construction for occupancy in late 2020.

The challenge with high-rise development is protracted entitlement and construction schedules—it can take 3 to 4 years to go from concept to closing. Only two new condominium projects are expected to deliver before 2020, including Gridiron (recently completed) and NEXUS (delivery Fall 2019). Unsurprisingly, less than 10% of these 496 units offered for sale remain available. The supply and demand imbalance can also be felt in newer condominium buildings like Insignia and LUMA, where more recent sales have averaged a 25% price premium above their presale values. The tides are rising.

Greater affordability may be delivered by living in exurban communities, but not all consumers can afford the time it takes to commute. Sound Transit 3, a $50 billion+ transportation initiative, will eventually provide solace, however, the urban core markets will not face much competition from transit-based development until 2030 (once expanded new train schedules and consumer psyches harmonize). At least one new condominium development, Sonata, is being planned for Columbia City alongside the current LINK Light Rail line. While not technically urban, this format of housing will offer much needed affordability within an authentic “Main Street” community offering quick access to downtown Seattle jobs.

Wood frame condominium development is also expected to reboot in close-in, lower-zoned neighborhoods like Capitol Hill and First Hill. Several developers are exploring new projects that will offer attainable price points in studio, urban one bedroom and efficient one-and-two-bedroom flats. These developments are expected to average $1,000 per square foot or around 20% less than their high-rise alternatives, not to mention much quicker deliveries. It should be noted that The Cove, an apartment building, recently sold for a record $920 per square foot as an income property on Capitol Hill. This also evidences the stress test developers face justifying condominium premium (and regular income tax) vs. selling the same product to a single investment group as a capital gain with less liability.

PICTURED ABOVE: Capitol Hill and First Hill are expected to see a rise in wood frame condominium development, with projects such as SOLIS.

One headwind to the approaching condominium cycle is a correcting apartment market. If rents become more affordable, some prospective buyers may sit tight and take advantage of new project lease up concessions. With more than a dozen luxury apartment towers soon to deliver, supply may drive vacancies to more than 10% by 2022, although job growth and rental demand has been difficult to forecast with rapidly growing tech firms. Rent growth is plateauing and cap rates are rising so construction lenders are limiting the financing options for apartment developers. Some hold permitted, shovel-ready projects may need to sell to a condo developer or consider building out the condominium exit or risk losing their entitlements and market position. Not all developers can shift to a condominium exit midstream, however. Both architects and contractors are highly sensitive to condo liabilities and many specifically restrict the option of condo conversions. The first responders will benefit the most, given there is clearly a lack of attainably-priced new homes available before close of 2020.

Seattle’s lack of condominium development isn’t a function of demand so much as a developer preference. Merchant builders and equity funds aren’t in public service—they seek the highest return with the lowest risk, period. Fast rising rents and lower cap rates have made speculative development or build and hold strategies successful. And until recently, the sustained rate of presale price appreciations required for condominium development just weren’t demonstrated, in part because so few projects were delivered.

Besides, developers lament the Washington State Condominium Act, which limits presale buyers at risk to 5% earnest money deposits while the developer is required to fund 100% of the capital stack. Buyers can rescind at any time so the developer never really knows how sold they are. Essentially the consumer protection policies work so well for buyers that it scares developers. So, unless the gains are significantly better to warrant the risk, apartments win.

In fairness, demand for rental housing has been, and will continue to be, sky high. The job growth in Seattle, led in large part by Amazon’s meteoric growth alongside other tech titans, has drawn thousands of new residents who are more likely to rent initially than purchase. Between 2012 and 2017 there were more than 300,000 jobs added to the Seattle-Bellevue-Everett metro area. Corporations are attracted to Seattle because of the available talent, relative affordability and lack of a state income tax, making it easier to recruit and retain employees to the area than say, the Bay Area. These fresh employees are new to their city, however, so staying nimble is prudent. Statistically, it’s not until they settle down, couple up and vest in stock options that they become more inclined to buy—a process that may take a few years. But it’s been more than a few years since this apartment boom began, so that suggests that downtown Seattle may be incubating thousands of would-be buyers. From a unit perspective, if just 6% of renters occupying recently built apartments delivered in 2010-2018 decided to buy, the remaining pipeline of condos through 2022 would be sold out. Historically, household formation garners at least 50% ownership rates so therein lies the conflict, an imbalance with development practices.

Interestingly, rent growth in Seattle has eclipsed condominium value increases. In 2000, the average price square foot of a condominium was $351, while a monthly apartment rent averaged $1.58 per square foot. Rents today now average $3.05 citywide (closer to $4.00 in downtown Seattle), an increase of 93%, while condominiums typically fetch $568 per square foot, representing an increase of 62% over 2000. A lack of supply is also responsible for holding down values, but that’s about to change as new condominiums deliver. The median price of resale condominiums is rising more quickly nowadays, accelerating by 13% in the first half of 2018 over the prior year.

Townhomes also contribute to homeownership opportunities, however since 2010 they’ve only delivered about half the total unit supply in the core neighborhoods of Capitol Hill, Cascade, Central District and Lower Queen Anne when compared with the downtown condominiums. Given they are typically multiple levels and substantially larger, townhomes almost never offer new options priced below $700,000. Looking ahead, experts believe the production of new townhomes will actually decrease given the lack of suitable land options.

In addition to these market pressures, the rising cost of land, entitlements and high-rise construction are further driving condo values higher—recently matching median home price increases annually. By example, prior projects like Insignia and LUMA were presold at values that averaged $775 per square foot when they closed in 2015 and 2016, respectively. Gridiron closed earlier this year at values averaging $900 per square foot and NEXUS is expected to average more than $1,050 per square foot when it closes in late 2019. Newly reserved projects like KODA are averaging even more with soon-to-be launched presales at taller, view-oriented developments like The Emerald and SPIRE commanding in excess of $1,200 per square foot when closed in 2020. If that sounds high, it’s actually not. West Coast peer cities like San Francisco and Vancouver, BC are routinely commanding $1,500 per square foot values on new properties with luxury sales in excess of $3,000 per square foot.

Condominium development is an important yet relatively underserved component of the Seattle housing market. It allows for high-density housing within the urban core where the jobs are, dramatically lessening commutes and revitalizing urban villages. In addition, it permits local government the opportunity to incentivize developers through rezoning and height bonuses. It also offers attainable price points for homeownership as efficiently-scaled floor plans and robust amenities grant both a new place and way to live. Condominium development further provides affordable housing through the recent adoption of HALA (Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda) and adds incremental tax revenue to the city to support social services, while adding stakeholders to the skyline who are individually invested in the community.

A new condominium cycle has arrived, and developers need to catch up to the demand as prices are projected to climb faster than the supply can balance the playing field.